Challenge: Can we use snap-through to toughen graphene nanolattices?

Through

- mechanism-inspired structure topological design,

- molecular dynamics simulations,

- theoretical analysis, we present a novel design of 3D graphene nanolattice that can

- have multiple stable states with snap-through instability

- demonstrate pseudo plastic deformation and hysteresis to effectively dissipate deformation energy and tolerate crack-like flaws.

Unit cell design: build a nano-straw

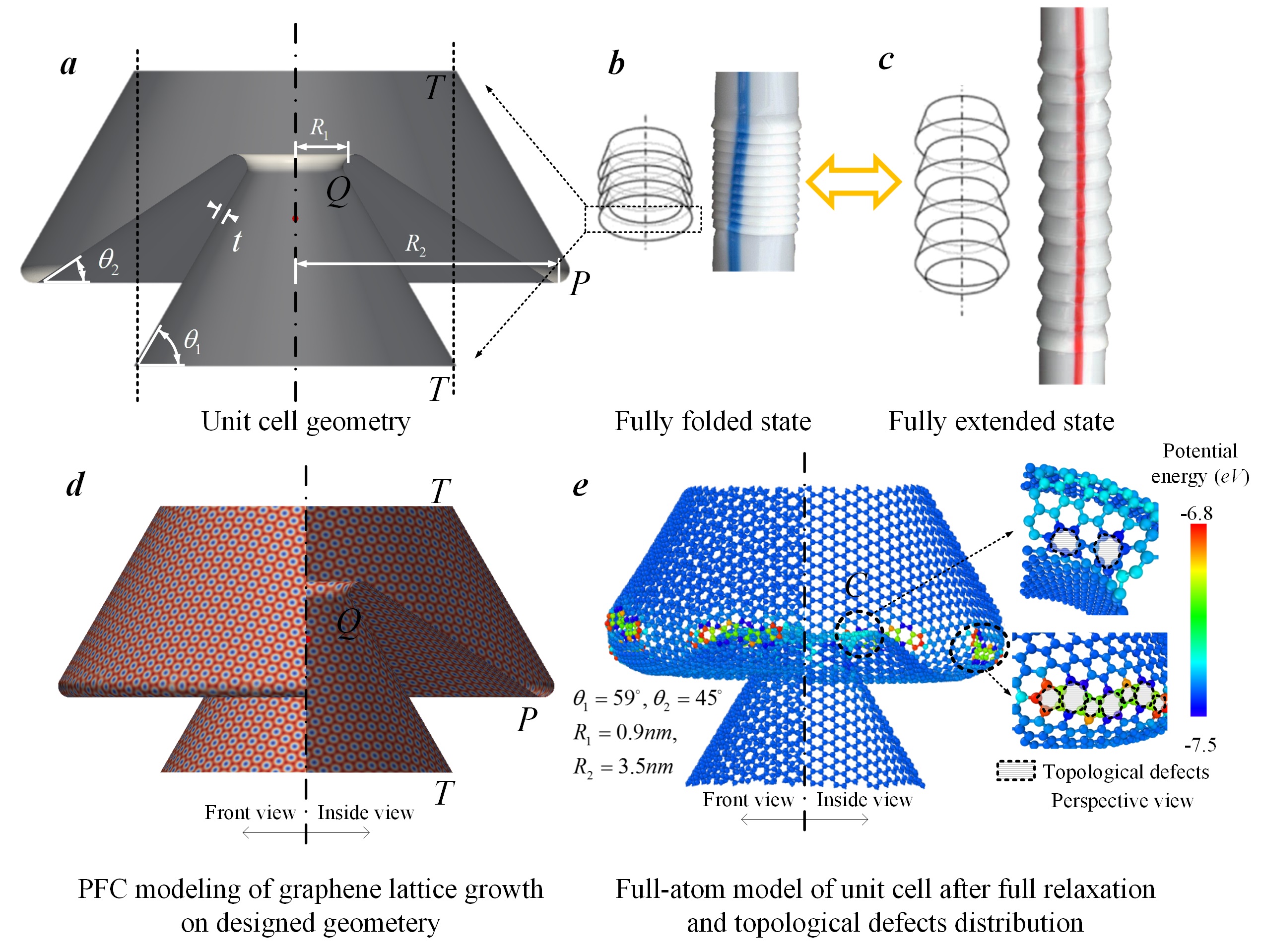

Fig. 1. Unit cell of shell structure in flexible straws and its nanoscale graphene counterpart engineered via topological design. (a) Geometry of the unit cell structure in straws. (b-c) The fully folded and fully extended states of flexible straws. (d) Phase field crystal simulation of a 2D crystal sample growing on the designed shell surface. (e) The atomic structure of the graphene unit cell with straw-like geometry after MD relaxation and the topological defects distributed at the inner and outer folds.

Fig. 1. Unit cell of shell structure in flexible straws and its nanoscale graphene counterpart engineered via topological design. (a) Geometry of the unit cell structure in straws. (b-c) The fully folded and fully extended states of flexible straws. (d) Phase field crystal simulation of a 2D crystal sample growing on the designed shell surface. (e) The atomic structure of the graphene unit cell with straw-like geometry after MD relaxation and the topological defects distributed at the inner and outer folds.

At macroscale, the flexible straw [43, 44] can change length by transforming between the folded state and the extended state (Fig. 1 b and c). The states are mechanically stable [45]. Here, we constructed a full-atom model of graphene counterpart to such a unit cell by taking advantage of the methodology of topological design [46-48], which includes

- phase field crystal modeling [49-51] of growing 2D crystal on the designed geometry of the conical frustra (Fig. 1 d),

- thermal relaxation of the obtained crystal structure via MD. Unit cells with straw-like topology are constructed with graphene (which may be the thinnest straw).

These graphene straw unit cells can distingush from their conterpart at large scale due to

- the presence of topological defects [46, 53], such as disclinations and dislocations, at the connections of the two frustra to accommodating and stabilizing the curvature transition (Fig 1. e),

- the residual stess coming with the topolgoical defects,

- the Van der Walls (VdW) interactions [54] between graphene surfaces.

The inevitable presence of topological defects, their residual stress [47] as well as the Van der Walls (VdW) interactions [54] between graphene frustra make the atomic sample different from its counterpart at large scale.

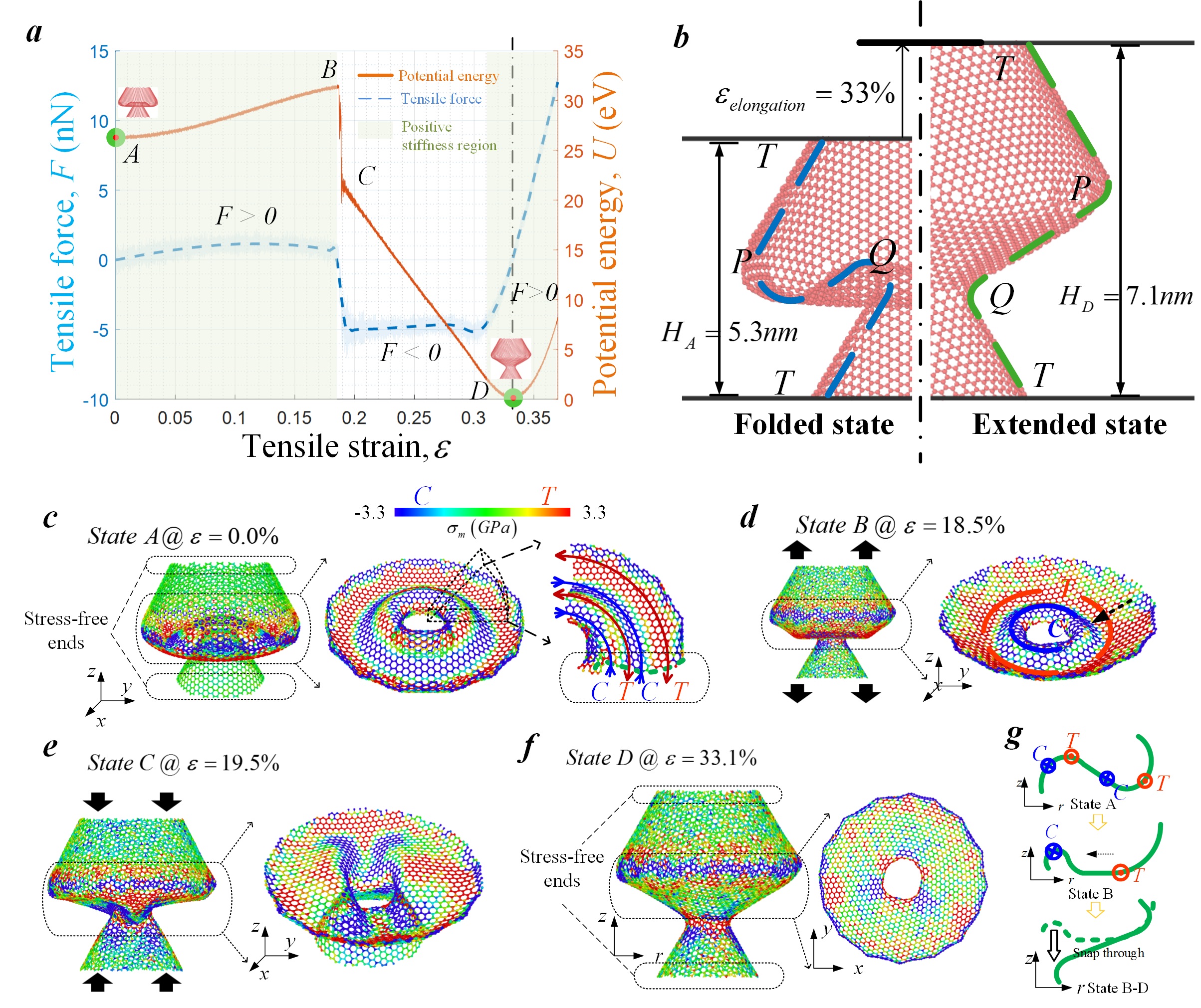

Fig. 2. The two stress-free stable configurations of the unit cell and the process of a snap-through event. (a) The force-strain and potential energy-strain curves of the unit cell transforming from the folded state to the extended state. (b) Geometry of the two loading-free equilibrium configurations of the unit cell. The two halves of the unit cell are in the folded and extended states, respectively. (c-f) Snapshots of a snap-through event during a tension test in MD simulation. (g) 2D sketch of the deformation process of the inner frustrum during the snap-through process.

Fig. 2. The two stress-free stable configurations of the unit cell and the process of a snap-through event. (a) The force-strain and potential energy-strain curves of the unit cell transforming from the folded state to the extended state. (b) Geometry of the two loading-free equilibrium configurations of the unit cell. The two halves of the unit cell are in the folded and extended states, respectively. (c-f) Snapshots of a snap-through event during a tension test in MD simulation. (g) 2D sketch of the deformation process of the inner frustrum during the snap-through process.

Can it snap?

By pulling the unit cell via MD, we observe

- the snap-through between the folded state and the extended state,

- force-strain and potential energy-strain curves. Indeed, there exists two mechanically stable states and the sample snaps between them.

How does it snap?

As shown Fig. 2 c and d, the snap-through event mainly takes place at the inner frustum (P-Q in Fig. 2 b) with the outer frustum (Q-T-P in Fig. 2 b) serving as a constraint to its deformation.

- At the folded state, the inner frustum is already self-stressed under no external loading (Fig. 2 c).

- At the critical moment, the axial-symmetry of the deformation is broken (Fig 2. e) and the inner frustrum flips out (Fig. 2 f).

- Compared to the folded state (Fig. 2 c), the residual stress in the inner frustrum is reduced in the extended state (Fig. 2 c and f).

In the following section, we combine the unit cell with different lattice designs to construct 1D and 3D graphene nanolattices and study their collective deformation behaviors, aiming at engineering effective energy dissipation by leveraging the effect of the snap-through instability.